Most people think about beautiful but dangerous female mermaids when they hear the word siren. But what about their male counterparts? Were there also male sirens in Greek mythology?

Male sirens existed besides female sirens in early ancient Greek mythology. The male siren was commonly depicted as a half-bird creature similar to the female sirens except that they had beards. However, with time they disappeared and eventually, sirens were only seen as dangerous mermaids.

In the following, I will show how exactly male sirens looked like and why they disappeared over the centuries.

Were there Male Sirens in Greek Mythology?

First, it is important to distinguish between the kind of siren we know today and what they actually were thought to look like in ancient Greece.

Today, we often imagine sirens as female mermaids who can turn dangerous, as in the TV show “siren”. But as I explained in my article about why sirens are not mermaids, the original sirens from Greek mythology were not mermaids at all but half-bird creatures.

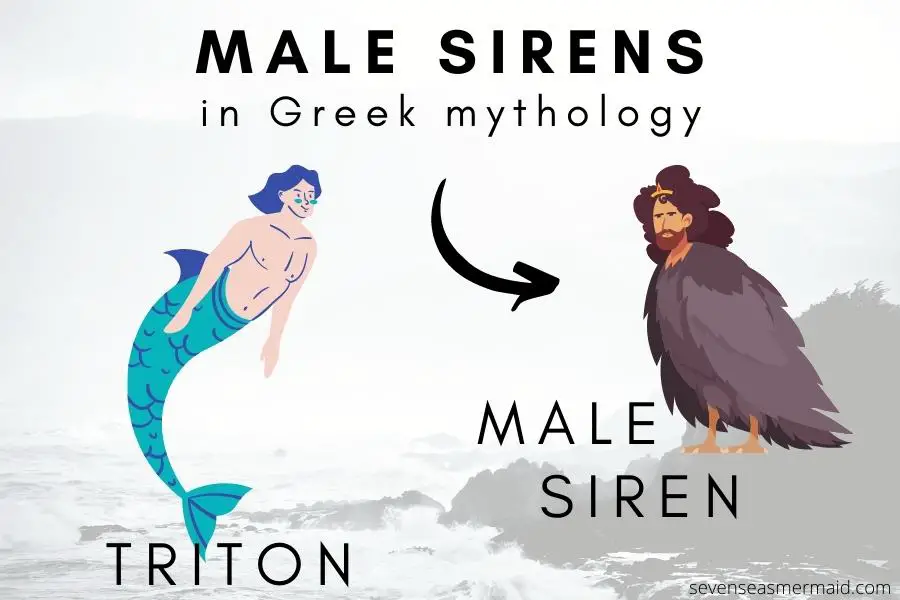

For the mermaids, it is true that they had male counterparts with fishtails. They were called the Tritons as they were the sons of the ocean god Triton.

However, as mermaids were not the same as sirens in Greek mythology, we will only talk about the original sirens here.

These ancient sirens were not solely female. Male sirens were just as commonly depicted in early Greek art. Here is one of these depictions:

As you can see, the male siren was depicted as a bird with a male head with a long beard.

The Roots of Bearded Male Sirens in Mythology and Art

Male sirens were seen as the same as the female versions at first. They were soul birds as their task was to accompany the souls of the deceased to the otherworld. You can read more about them in my article about whether there is some truth behind the myth of the dangerous sirens as we know them.

Therefore male sirens did not have a separate name. They were simply referred to as “sirens” as well.

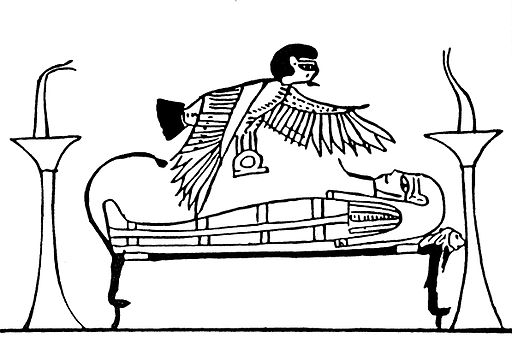

In fact, the first sirens in Greek mythology might have been thought of as male. It is believed that the ancient Greek idea of sirens (as soul birds) was influenced by ancient Egyptian ba-bird who were depicted as male as well.

These ba-birds from Egyptian mythology were thought to represent a part of the soul of a deceased person which could leave the body and ascend to the sky. They were usually depicted as a man-headed hawk:

In ancient Greece, the sirens were a popular motive on Corinthian vases. You can find male as well as female sirens on the vases that still exist today.

However, around the 5th century BC, the male sirens disappeared from Greek art and from then on, only female versions of sirens were depicted.

Possible Reasons why Male Sirens Disappeared

The exact reason why the sirens were not depicted as males anymore after the 5th century BC is not clear because no written explanation was ever found.

However, it is believed that the female sirens might have become more popular because they were seen as a new Greek version that was distinct from the Near Eastern male soul birds. Thus, people might just have liked the idea of female sirens more than that of male sirens.

Maybe the hugely influential description of the sirens in the Odyssey by Homer also played a role in this shift towards only female depictions. This play from around 700 BC is the most famous literary source that describes the sirens.

While the sirens are actually not physically described and their gender is never mentioned, the story makes the reader assume that they are females.

It seems the Greek people agreed and the male versions of the sirens were eventually forgotten as they did not appear in art anymore.

The depiction of the female sirens however kept changing – from bird depictions with female heads to women’s bodies with just wings and a bird body from the waist down:

The last change in the appearance of the sirens did however not take place in ancient Greece. During the Middle Ages, they were first depicted as mermaids which remained how we think about the appearance of sirens.

References:

https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/now-at-the-met/2018/dangerous-beauty-interview-with-kiki-karoglou

https://www.britannica.com/topic/ba-Egyptian-religion

Tsiafakis, “‘ PELORA ‘,” in Padgett, The Centaur’s Smile , 75.